Infodumping, Emotion Dysregulation, and Writing Fiction

A conversation with ChatGPT

For a while, I've been struggling with two problems with my writing.

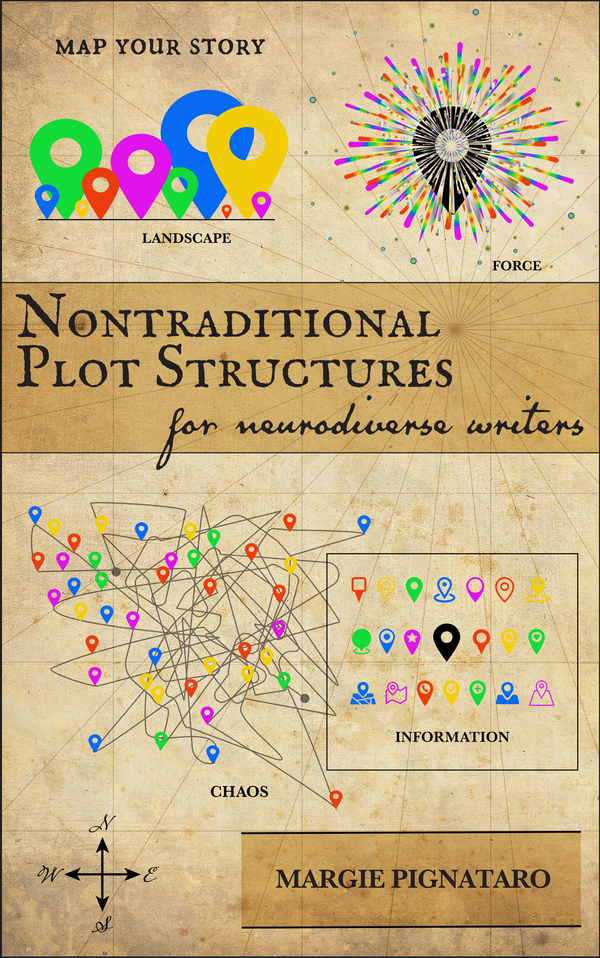

The first problem is that I love infodumping and I'm not entirely sure how to write it in fiction. I have ideas, and I know it has something to do with encyclopedias, documentaries, and journalism. I have all of the pieces. I came up with an Information plot structure as a guide. But nothing has clicked. I don't know how to assemble the pieces.

The other problem is truly difficult. Three years ago I started an animated series about the medieval black plague. I wrote 800 pages in four months and then had to stop. It became emotionally overwhelming and even traumatizing.

I absolutely do not want to abandon my series. This isn't about the sunk cost fallacy. I'm still very invested in the story. I think about it often. It's important to me, but I don't know how to work with it.

I've felt these two issues are somehow linked, but I couldn't think it through.

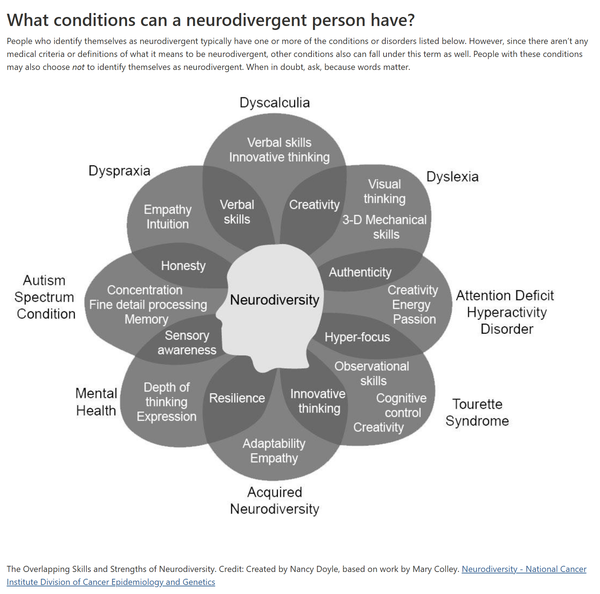

I'm neurodivergent and I love both infodumping and reading or hearing infodumps. There must be a way to structure an infodump that will engage a reader. I want parameters more specific than "be interesting" or "shorter paragraphs". So I decided to consult with ChatGPT.

I know there's a lot of hate for AI's right now, and with valid reasons, but I have rules about using ChatGPT:

- Full disclosure. I cite ChatGPT whenever I use it, just like any research source.

- No ghostwriting. I don't have ChatGPT write posts or stories or whatever. I didn't spend 20 years in college just to have an AI write for me.

I like asking ChatGPT for breakdowns because what I receive are collages of ideas from a broad range of (not cited) texts. I don't have any guarantees that this information is 100% accurate, but it sounds accurate. These characteristics about infodumping sound like they're taken from several writing resources and I've heard similar things in the past.

ChatGPT can be verbose, even in its brevity, and I've edited this conversation. Here is the link to the entire text.

I started at the very beginning.

I asked ChatGPT, “What is infodumping?”

Infodumping is when a writer gives the reader a big chunk of background information—facts, history, or worldbuilding—all at once, usually in a way that interrupts the flow of the story.

It’s common in fiction (especially fantasy, sci-fi, and mystery) when the author wants to explain the setting, a character’s backstory, or the rules of the world. But it can also show up in nonfiction if a section suddenly overloads the reader with dense, contextless facts.

Typical signs of infodumping:

- The pacing slows to a crawl.

- Characters stop acting and start “lecturing.”

- Information isn’t woven into the action or dialogue.

- The reader feels like they’re reading a textbook instead of a scene.

Writers usually avoid infodumping by:

- Drip-feeding info over time.

- Embedding facts in action or dialogue.

- Letting the reader infer details rather than stating them outright.

I thought ChatGPT would define infodumping and its relation to neurodiversity, but it assumed I meant fiction writing. Lately, I've been asking ChatGPT many questions about The Great Gatsby for a future post, so it probably assumed that's what I wanted.

These characteristics are centered on actions and maintaining a fast pace. This is very traditional. It fits with a traditional Journey plot.

ChatGPT didn't offer anything nontraditional, unique, or creative. This is a strict list of "this is good" and "this is bad". (Actually, it's all "this is bad".)

The list is also focused on a neurotypical paradigm: be subtle, have subtext, put the characters first, and avoid any kind of encyclopedic or journalistic structured writing.

Essentially, information is a necessary evil in a story. Hide it in plain sight, so your reader won't get bored.

This is a form of anti-intellectualism.

What if neurodivergent writers want to lean more towards an encyclopedic or journalistic structured style because the emotional, action-based structure traditionally used doesn't feel right?

ChatGPT, in its inimitable, sycophantic, and servile style, asked if I wanted tricks to avoid infodumping, as well as “a plug-and-play template you can use to turn a raw list of facts into a long, engaging infodump without losing the reader’s interest.”

Of course, I do, ChatGPT.

I present this to all neurodiverse writers who wish to turn their organic infodumps into "interesting", active moments:

Atmospheric Infodump Template

1. Hook / Opening Line

- Start with a striking image, contradiction, or mystery.

- This pulls the reader into the “lecture” without them realizing it.

- Formula: “No one remembered [X]. At first, [misconception].”

2. First Layer of Facts (Low Stakes)

- Introduce the first key fact gently, through perception or rumor.

- Keep it tied to how people experienced it at the time, not a dry statement.

3. Escalation (Rising Stakes)

- Add the next fact, but make it worse than the last.

- Use sensory detail (sight, sound, smell, touch) or metaphor to keep the mental image alive.

4. Midpoint Punch / Turning Point

- Insert a dramatic event or decision that feels pivotal.

- This is where you drop your most striking image or emotional hit.

5. Climax of the Infodump

- The largest, most damning fact — or the emotional core — lands here.

- Often it’s the cause of the earlier events, saved until the end for tension.

6. Reflection / Aftermath Line

- End with a line that connects the info back to the narrator’s worldview or the story’s themes.

- Gives the block a sense of closure.

Fill-in-the-Blank Version

No one remembered [event in broad, mysterious terms]. At first, [common belief or misconception], and people [small-scale response or coping mechanism]. But by [time escalation], [larger consequence described with imagery or sensory detail]. That was when [major decision or turning point, described vividly]. [Optional: short reaction line from narrator]. By the end, [final shocking fact or reveal], and [emotional or philosophical reflection].

I have to admit, this would be a good writing exercise for any writer. It's like a math equation or the instructions for Ikea furniture. Doing this exercise a few times will plant seeds and grow through a writer's unconscious processes.

If you’re writing for neurotypicals, if you are neurotypical, this should work well for you.

I’m not writing for neurotypicals and I’m not neurotypical and this confuses me. I get what the template is laying out, but this does not feel intuitive, creative, or real. I hate to use the word "authentic", so I'll say, this just doesn't feel right.

This is a round hole, and I feel like a rhombicosidodecahedron-shaped peg. (Don't all neurodivergent people, though?)

I wanted to turn the conversation back to my original intentions, so I asked ChatGPT, “what is infodumping in reference to neurodiverse people”.

The response surprised me with its passionate validation of neurodiverse individuals:

When people talk about infodumping in a neurodiverse context, they usually mean something quite different from the writing term — it’s a social/communication style, not a storytelling flaw.

Definition in neurodiverse communication

For autistic, ADHD, and other neurodivergent people, infodumping often means sharing a large amount of detailed information about a topic they care about, all at once, usually with enthusiasm and without much filtering for what the listener already knows.

It’s not “bad” — in fact, it can be:

- A way to share joy and excitement.

- An act of connection and trust (“I feel safe enough to tell you everything I know about this thing I love”).

- A stim or self-soothing behavior, especially if the topic is a special interest.

Why it happens

- Many neurodivergent people have deep, detailed knowledge of their special interests.

- They often think in connections — one detail leads to another, which leads to another.

- Filtering or “trimming” the info can feel unnatural or even frustrating, because all the details feel important.

How it feels

- To the infodumper: energizing, engaging, sometimes hard to stop once started.

- To a receptive listener: fascinating and intimate — like getting a backstage tour of someone’s brain.

- To an unprepared listener: overwhelming if they’re not in the same mental space or topic interest.

In community culture

Among many neurodivergent people, “infodumping” isn’t an insult — it’s a word reclaimed to describe a valued way of connecting. People might even say things like:

- “I love when you infodump about space stuff.”

- “Thanks for letting me infodump — I needed that.”

It’s often paired with active listening signals (“Please keep going,” “I’m still following”) to help the infodumper feel comfortable sharing.

If you want, I can also give you a side-by-side showing how infodumping in fiction writing and infodumping in neurodiverse conversation are similar and different — they actually overlap in some surprising ways.

I said, yes, of course.

Overlap:

- Both involve a flood of information.

- Both work best when there’s a reason for the audience to care.

- Both can be engaging or overwhelming, depending on timing and delivery.

Key difference: In fiction, infodumping is judged by how it affects pacing and immersion. In neurodiverse conversation, infodumping is judged by how it affects mutual connection.

There’s a problem here.

When we’re talking about a fictional infodump, it can feel “dry” and "disruptive" to pacing if not “handled well”. An audience needs “a reason to care”. The dump shouldn’t be “too long or detached from the action”. It’s a “flaw” unless it’s done “artfully” (ChatGPT fails to explain what "artfully" means). And the information should be important to and intertwined with the action.

However, for a neurodiverse infodump, it’s different. It’s “energetic, passionate, and fueled by genuine interest”. It’s a sign of “trust, excitement, and bonding”. But, people can become bored if uninterested, and one should check in to see if “they want to hear more”.

In fiction it’s a liability; in a neurodiverse individual, it’s a positive, passionate bonding moment that is part of our culture.

Both of these cannot be true.

In fiction, there is a long standing dedication to a neurotypical, traditional Journey structure. Built into this structure are rules about fast pacing, actions, goals, and emotional investment. Infodumps do not give people "a reason to care" because they aren't "active". This is a neurotypical paradigm.

Neurodiverse writers struggle with this structure. We are taught that this is the only way to write a good story and we must conform to it.

Yet, one of the core characteristics of a neurodivergent person is the love and comfort of an infodump, and this is considered a good, intimate thing. ChatGPT encourages open-mindedness to neurotypicals when experiencing an infodump. Yet ChatGPT also provides a piece of etiquette to the neurodiverse speaker: "use signals to check if the listener is engaged (or ask if they want to hear more)". This still betrays a bias, that an infodump is boring.

I've spoken to MANY, MANY neurotypical people who are not infodumping, but are boring as shit. I rarely have been asked if I want to hear more.

This isn't really about infodumping: this is about people being assholes.

I decided to look at this a different way.

I asked, “How can we write an infodump that doesn't involve the main action of a story or characters, yet the audience will still care?”

If you want to write an infodump that’s detached from the main action and characters but still keeps the audience hooked, you’re essentially writing a standalone block of exposition that earns emotional investment on its own.

That means you have to replace “caring about the characters” with other hooks: mystery, emotion, stakes, and voice.

Here’s how:

1. Treat it like a self-contained story

- Even if it’s pure exposition, structure it with a beginning, middle, and end.

- Open with a problem or oddity, escalate consequences, and end with a reveal or turn.

- The audience stays because they want the payoff.

Example: “No one knows who built the Black Tower… but every hundred years, the bells toll — and someone dies.”

2. Use the “legend” or “document” frame

- Make it feel like the audience is reading a lost scroll, a historian’s entry, or a local’s fireside tale.

- The frame gives the block a reason to exist in the story world, even if no characters are actively “doing” anything in it.

3. Anchor it in emotion, not just facts

- Facts alone fade. But if you present those facts through awe, horror, or wonder, the reader feels something.

- Ask: How would someone who lived through this describe it? Even if that someone is fictional.

4. Seed unanswered questions

- Drop a strange detail without explanation so the audience keeps reading for resolution.

- Make the reader think: Wait, why did they burn the sky? and promise to tell them later in the block.

5. Give the block a distinct voice

- Make the “narrator” of the infodump interesting in their own right.

- They can be cynical, reverent, fearful, arrogant — anything but blandly neutral.

To quote Lt. Joe Kenda, "Well, my, my, my. This interests me."

I pushed it to the logical outcome.

This is really helpful for neurodivergent writers. It also brings us to an idea I had been toying with:

Write a fictional story structured like an encyclopedia, a news article, a documentary, a historical or religious text. Mystery is the best way to maintain interest because it doesn't require anyone to "care" about a character, nor depend upon emotional turmoil, which can be a very real and distressing experience for a writer. This happens to me.

I asked ChatGPT how to structure a documentary, feeling this may enlarge the discussion. It did and, after going back and forth, what followed is pure gold:

If you want, I can map this documentary structure directly onto your “novel-length infodump” idea, so the whole thing reads like a sweeping historical documentary transcript — even without active characters. That way, it feels immersive but stays factual.

You said:

yes

ChatGPT said:

Alright — here’s how you could structure your novel-length, no-character infodump so it feels like a sweeping historical documentary transcript.

I’ll base it on documentary storytelling principles so the reader experiences the same sense of discovery and immersion they’d get from a visual doc — just in prose.

Documentary-Style Novel-Length Infodump Structure

I. Opening Hook – “The Cold Open”

Purpose: Grab the reader immediately with a striking fact, quote, or mystery.

- Drop them into the middle of an event or an image that encapsulates the whole work’s tone.

- Give no context yet — intrigue first, explain later.

Example:

“When the bells tolled for the seventh time, the city was already gone. No one saw the flames. No one saw the sky change color.”

II. Introduction / Prologue

Purpose: Establish scope, tone, and central question.

- Present the subject (e.g., the fall of an empire, the history of a lost continent).

- Hint at the importance — why this matters to the reader’s understanding of the world.

- Act like the narrator is the “documentary voice” — confident, authoritative, sometimes poetic.

III. Act 1 – Foundation / Origins

Method: Chronological or thematic opening.

- Describe the earliest known origins of the subject.

- Include myths, archeological records, or conflicting accounts.

- Use a mix of vivid description and “source quotes” (fake excerpts from scrolls, letters, oral tradition) to mimic a doc’s cutaways.

IV. Act 2 – Expansion / Height

Method: Show how the subject grew, evolved, or reached its peak.

- Use “archival” style storytelling — describing artifacts, ruins, or cultural practices in detail.

- Insert sidebars or “interview transcripts” from fictional scholars or eyewitnesses.

- This is where lush worldbuilding lives: geography, politics, economy, religion, art.

V. Act 3 – Tension / Decline

Method: Introduce instability or approaching change.

- Present multiple theories about why things started to go wrong.

- Let your “narrator” acknowledge gaps in the record, hinting at lost knowledge.

- Use recurring motifs for atmosphere (e.g., each section opens with weather reports, omens, or population tallies).

VI. Act 4 – Collapse / Turning Point

Method: Give the major event or catastrophe in detail.

- Stay descriptive rather than “active scene” — keep the documentary tone.

- Intercut “eyewitness-style” fragments with wider analytical narration.

- Maintain suspense even though the outcome is known.

VII. Act 5 – Aftermath / Legacy

Method: Show what remained — ruins, legends, lasting influence.

- Use artifacts, place names, or cultural echoes to make the world feel lived in.

- End with unresolved mysteries so the reader’s imagination keeps going.

VIII. Closing Statement

Purpose: Leave the reader with a thematic conclusion or haunting final image.

- Could be reflective (“History remembers the victors… but the victors are dust.”)

- Or speculative (“And if the bells toll again, we will know they have returned.”)

Tips to Make it Feel Like a Documentary

- “Primary source” inserts: fake journal excerpts, letters, stone inscriptions, newsreel transcripts.

- Multiple voices: let “experts” contradict each other to mimic scholarly debate.

- Recurring visual/sensory motifs: just like a film would reuse certain shots.

- Section titles: use time periods, locations, or key events to orient the reader.

This is what I want. This makes perfect sense to me.

The way to deal with emotion dysregulation is to separate myself from the characters emotionally. Referring back to my 800-page black plague series, I became too emotionally invested in the horrors my characters are experiencing.

By writing the with distance, via intertextuality and characters who rarely speak for themselves in social situations, I will drain some of the intensity. Not all of it, though. Information about people dying in an agonizing way is still intense. We don't need to feel every horror to empathize or care.

And we do experience what fictional characters feel. Mirror neurons accomplish this:

The phrase "mirror neurons" refers to neurons in the frontal cortex that fire both when you do something and when you see someone else doing it...In short, mirror neurons provide us with an "embodied simulation" of not just the actions but the thoughts and feelings of others. We share them in our bodies.

If we see someone throwing a baseball, our brain activates the center involved in throwing a baseball, but without us actually doing the action.

If we see someone die in pain, we also experience that pain and horror on some level, but without actually feeling it.

Imagine someone writing about being sexually assaulted, in a realistic, Journey-structured story. They go into explicit details, describing every awful feeling during and after. A friend of mine expressed that this kind of structure is necessary to talk about rape because it will make readers understand and feel empathy.

Are we so jaded that we cannot sympathize or empathize with someone who has been sexually assaulted unless we have every horrifying detail?

There are benefits in emotionally charged stories. They do strengthen empathy and teach us more about social interactions and the experiences of others. But they aren't always necessary.

Are we so desensitized to other people's agony that we have to relive it with them?

But for someone who is neurodivergent, an emotionally realistic story can be too intense and too real. I don't know why, but I know I'm not the only person who reacts to fiction in this way. (If you do, too, please comment below.)

Infodumping creates a buffer. It's not a complete emotional blockage. There is more than one way to tell a story, and neurodivergent writers should tell their stories in ways that they feel comfortable.

I will read this a few times, go away, think about other stuff, and then return and see what works and doesn't for me.

Which is the best way to handle any advice or theory about writing.